Nobody Wants to Burn Out Anymore

You’ve probably heard it countless times: “Nobody wants to work anymore.” It shows up everywhere, from casual conversations to headlines and social media posts.

But here is the catch: this is not a new complaint. It is (way, wayyy) older than you think.

Before we get into it, a quick note about me: I am writing this as a student. I can work less than full time because my parents support me. That is a privilege, not a moral flex. I am not trying to speak for every young person. I am pushing back on a narrative that keeps getting recycled while the deal around work keeps shifting.

Also, I am going to mix countries and examples in this post. Some links are Austrian, some are German and some are US focused. The underlying pattern still matters, but the exact numbers and institutions differ by country.

Where does it come from?

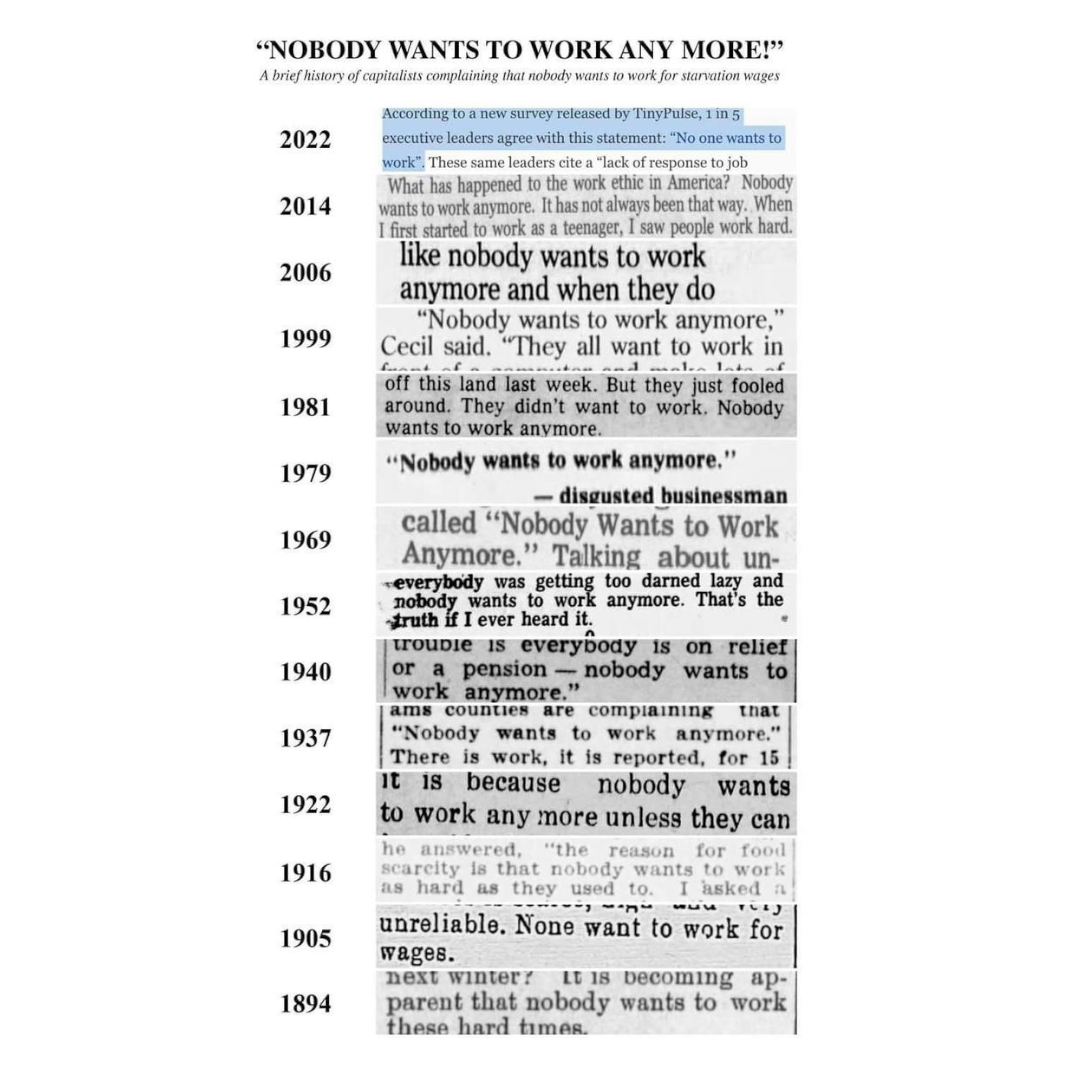

Take a look at the graphic below, or read Snopes’ detailed fact check with sources on the origin of the phrase “nobody wants to work anymore”. It shows that this exact phrase has been circulating since at least 1894. For over 130 years, people have accused younger generations of being lazy, entitled or unwilling to put in the effort.

And yet, generation after generation, people keep working.

So no, it is not really about work ethic. When someone says “nobody wants to work anymore”, what they usually mean is “nobody wants to work the way I had to.”

There is pride in hardship and there is also resentment that can show up when younger generations push back against norms that used to be non-negotiable. Add to that a reluctance to acknowledge that the economic and social reality has changed. Housing prices are astronomically higher in Austria according to Statistik Austria. Job security is increasingly fragile in many sectors, as discussed in a research review on job security and insecurity. Wages and bargaining power have also been a pressure point for a long time, with discussion about long term labor movement effects in this working paper by Cullen.

It is easier to frame all of this as laziness than to admit that the system people are inheriting is often tense, expensive and disrespectful. Surveys of people who actually quit jobs tend to point to low pay, no advancement and feeling disrespected, as summarized in Pew Research Center’s survey on why workers quit in 2021.

Why it can look like nobody wants to work

If you work in hospitality, retail or any kind of service job, the frustration is real. Places are understaffed. Waiting times are longer. People quit and do not come back.

Sometimes you also meet people who are unreliable, checked out or genuinely done. That happens.

A lot of this debate is also about visibility. Plenty of young adults spend longer in education. Many work part time while studying, then disappear during exams, internships or thesis phases. If you are the person trying to staff a shift, that can look like “nobody shows up.”

Demographics matter too. If a society gets older, you can get shortages even if nobody changes their attitude. So yes, the surface level impression has some basis. The question is what explains it best.

The shortage is not a moral failure

COVID did not create these tensions, but it cracked them open. What many commentators called “the Great Resignation” often looked less like a tantrum and more like a reassessment, which is how the Financial Times described the phenomenon.

People had time to ask themselves whether they really wanted to return to jobs that left them drained, underpaid and barely able to keep up with their bills. A Pew Research Center survey of workers who quit in 2021 lists boring reasons: low pay, no opportunities for advancement and feeling disrespected.

Then you add inflation. Brookings discusses whether pay has kept up with inflation. If a job does not buy stability, and it also demands your health and your weekends, it is not a mystery why people avoid it.

It is not that people do not want to work. It is that people do not want to sacrifice their health, dignity and future just to stay afloat.

“Gen Z is lazy”

It is a tempting story because it makes the world simple. It also ignores what is actually happening.

For example, some recent reporting suggests that employment among younger age groups has risen in recent years, driven in part by students working alongside education. National Geographic Germany discusses how much Gen Z works compared to previous years and points to German labor market data.

That does not mean every young person is grinding 60 hours a week. It means the “they just do not want to work” storyline is a lazy shortcut.

Also, a lot of young workers are not rejecting work. They are rejecting bullshit jobs. By that I mean: low pay, high stress, no upside and zero respect.

Mental health is another factor that is easy to mock and hard to ignore. People still want to work, they just want more control over their time, which is the core argument in Harvard Business Review’s piece on control over time. Gen Z and Millennials also talk more openly about mental well being, and they are more willing to take time off when something is wrong, as described in Verywell Health’s report on Gen Z sick days.

This is not only a vibes argument. The American Psychological Association reports that Gen Z adults show high levels of stress and mental health symptoms compared to other age groups in their reporting.

If a job leaves people sick, numb or hopeless, maybe the question should not be “why do they not want to work?” Maybe it should be “why is this still considered acceptable?”

What people actually ask for

When people say they want “better work”, they usually mean boring basics: decent pay, predictable schedules, fair treatment and tasks that do not feel soul crushing.

That is not entitlement. That is a workforce reacting to incentives.

Worker surveys often mention flexibility as one of several reasons people leave or refuse certain jobs, including in Pew Research Center’s survey on job quitting reasons. In German speaking debates, you see similar themes around flexible work and fair pay in Der Standard’s article on Gen Z work expectations. You also see workplace orgs talk about what makes younger employees actually motivated in Great Place To Work Austria’s blog post on Gen Z effort and unions frame it as a necessary adaptation for employers in ÖGB’s commentary on employers needing to adapt.

Also, be careful with generational stereotypes in general. A useful discussion of that is the WSI Institute piece Jung, faul, wehleidig? Hat die Gen Z den Generationenvertrag gekündigt?. The point is not that one age group is great and another is bad. The point is that commitment, motivation and expectations depend heavily on conditions, life phase and culture.

Not every job can be remote. Not every workplace can offer full flexibility. Some work is physically hard by nature. That makes the question sharper, not softer: why are the jobs that must be on site so often the ones with the worst pay and the least respect?

So what is going on?

People do want to work. They just do not want to be treated like disposable parts in a machine.

So maybe the issue is not that nobody wants to work anymore. Maybe it’s that nobody wants to work like it’s still 1980 with worse rent and better coffee.

It is also worth saying out loud that a lot of the tension is about fairness. Many older workers suffered through inflexible jobs, toxic bosses and zero room to complain. In Austria, reforms associated with people like Bruno Kreisky shifted parts of that landscape.

So when a younger person says “no thanks” to the same misery, it can sting. It can feel like someone is skipping the struggle you had to endure.

But is that not the point of progress?

If the next generation can demand better working conditions, that is not a moral decline. It is a signal that the old deal stopped making sense. It is also a chance to rebuild it, instead of turning exhaustion into a tradition.

And yes, sometimes the criticism hits home for people like me, too. I get support. I get options. That is exactly why I am not buying the “everyone is just lazy” line. The problem is not young people. The problem is that too many jobs are structured in a way that only works if someone else silently subsidizes your survival, whether that is parents, a partner or your future pension.

Speaking of pensions: plenty of young people do not feel confident they will get one, and that anxiety is part of how they judge the tradeoffs of work and life, as discussed in VersicherungsFinanz’s piece on what young people expect and fear about pensions. Public discussions around early retirement in Germany also show how widespread the desire to exit earlier can be and how quickly debates turn into moral judgments, as covered by MDR on early retirement and policy debates.

If the promised finish line looks fuzzy, it is not shocking that people start questioning the race.